Spheres of Influence and the Attribution of Change

A lot of our initial conversations with clients start with some version of the following: “We really don’t know how to prove that we do x. We know that we see that change day to day, but we don’t have the data to prove that we caused that change.” The key word in this request, of course, is “caused.” Often, organizations feel pressured to demonstrate that their intervention was the sole cause of an observed change. Even when funders or stakeholders aren’t requesting that directly, it’s often assumed that “proving” that your intervention caused an observed change is still the “holy grail” of evaluation. Any grant writer or evaluator will tell you, however, that demonstrating that their program or service was the sole cause of a program is challenging, if not nearly impossible. This challenge comes down to two key concepts: attribution and contribution.

Attribution is claiming that your organization or program CAUSED an observed change in an individual, group, or community. Contribution is claiming that your organization or program HELPED TO CAUSE an observed change. To understand where we can claim attribution and where we must claim contribution, we can think about spheres of control, influence, and interest.

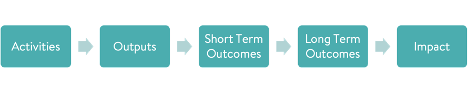

In a standard logic model framework, you have 5 main categories:

We often have some degree of control over the first two categories, activities and outputs. These categories articulate the things our program sets out to do (activities) and the extent to which we completed those things (outputs). We have a fair amount of control over these two categories; we can implement as many training sessions as we choose, for example, and to some degree, we can control how many people attend those trainings. It’s often safe to say that any changes in our activities or our outputs can be attributed to our organization’s actions, as these are within our sphere of control.

Once we move into short and long-term activities, we start to move into our sphere of influence. These categories articulate the actual change that we hope to see in individuals, groups, or communities - an increase in knowledge after a training, for example (short-term outcome) and then a change in behavior implementing that knowledge (long-term outcome).

To demonstrate attribution in short- or long-term outcomes, one must rule out any other potential variable. This is really only attainable by utilizing a randomized-control trial, or, at a minimum, matched comparison groups. However, designing and implementing these types of evaluation studies are costly, lengthy, and carry ethical considerations about who gets access to certain services. As such, they are often out of reach (or undesirable) for most nonprofit organizations. For these reasons, it is exceedingly difficult to claim that these changes can be attributed to our organization’s efforts.

Impacts, or community- or population-level changes that we hope to see as a result of our efforts, live within our sphere of interest, and can be even trickier to measure. Often, these outcomes are only obtainable through partnership with other organizations, or in some logic models, simply provide us a vision or a “north star” of what we hope to achieve so that we can stay focused on the bigger picture. As the interventions to “move the needle” on these outcomes are much more complex, it is nearly impossible to demonstrate attribution to one particular organization.

Demonstrating contribution, whether to short- or long-term outcomes (or even impact!), however, is much more straightforward. If our logic model is sound, and we have support for how each link in our logic “chain” leads to the other, we can often make a strong case for how a practice, program, or service contributes to a longer-term change. Developing this strong case requires the following:

Evidence to support that a short-term outcome has been shown to be predictive of a longer-term outcome (using more rigorous research studies);

A well-developed intervention that can be implemented to (some degree of) fidelity; and

A systematic and well-planned evaluation strategy to measure changes in outcomes.

Once these three conditions have been met, it’s then up to us to change how we communicate what we’re trying to achieve. If we set expectations that we can attribute change to our programs, when we don’t have the resources or the structure to do the kinds of rigorous evaluation that requires, then we are immediately setting ourselves up to miss the mark. If we’re clear, though, that we are part of a rich ecosystem of services and supports and that we expect our work to contribute to a particular outcome (and we can demonstrate that with relative consistency), then the argument for the impact of our intervention becomes much stronger, more transparent, and more easily measured.

So consider this your permission slip: frame your change in terms of contribution, not attribution, and be comfortable acknowledging to funders and other stakeholders that you recognize your organization's role in a broader system of resources working together to make the world a better place.

Blog by Amy Merritt Campbell